Many readers may frown and ask: Social psychology in sports?... What kind of territorial invasion is this? However, we must accept the premise, whose conclusions stem from surprising experiences. News reports have informed us of the presence of a psychologist in the Brazilian football delegation that competed in the World Cup. Some joked about it; others reported the news with astonishment. Europeans, accustomed to exploring every field of research, have received this innovation with great interest. It is already being stated that, both in Italy and France, future sports delegations will include a specialist in psycho-social matters.

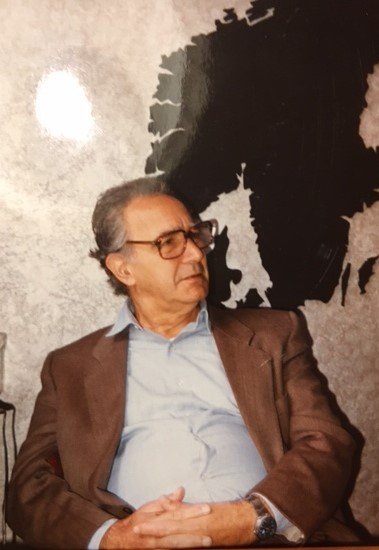

We, also driven by curiosity, have built a bridge between a scientist and public opinion. This scientist is Dr. Enrique Pichon Rivière, whose prestige as a psychoanalyst has gained worldwide recognition. Addressing the relevant topics, Dr. Pichon Rivière begins by telling us:

—Indeed, in our times, sports are of paramount concern. Everyone seeks to develop physical strength and endurance. Advances in science and mechanics have created numerous means that athletic training employs for its purposes, and in every country around the world, many governing bodies and clubs have been established to oversee, manage, and promote various sports activities. Established rules have, in turn, created a common uniformity for these practices. However, what has been little discussed is that the involvement of a social psychologist in the field of sports holds special significance today. This is because one of the most prominent figures in social psychology, George H. Mead, based his studies on observations made in team games, in which he himself participated.

—It seems to me that you are very interested in the subject. May I ask what led you to focus on it?

—I have practiced sports since childhood, particularly football. Moreover, I have lived in small towns with sparse populations, which naturally facilitated the formation of gangs or "crews," meaning spontaneous groups of children with a specific purpose. In Goya, Corrientes, for example, we founded a club, Matienzo, which became the most important in the area. I remember that, in those days, we constantly organized ourselves as a team—whether for playing, planning collective escapes to an island, engaging in naval battles on the river (to the great despair of our mothers), or any other adventure. Since then, I have carried with me the experiential awareness of the operational nature of group situations. Years later, sharing sports activities with my children, I have relived this experience.

—Is this the first time you are presenting ideas on this subject?

—Yes.

—Do you have any information on whether such work has been undertaken before?

—I have gathered some, but I am certain that nothing systematic has been done.

—In your opinion, doctor, what is the position of a team within an institution?

—A group or team that functions within a club must assume assigned roles and maintain a specific level of prestige.

—But... what about professionalism?

—With professionalism, this situation becomes considerably more complex. Because now, in addition to the team’s task of winning matches, there is also the need to sustain a certain level of performance, as their role has become a profession—a means of livelihood.

—There is no doubt that sports as entertainment have brought about a series of deeply ingrained issues.

—But there are other conflicting factors. Most of a team’s problems do not originate solely from within the team itself. Consider the commitments that club officials have and the secondary uses of sports activity (such as political projection). This means that each team member—the player—is caught in a web of tensions, which he often tries to escape from, though unsuccessfully. There is also another circle composed of coaches, physical trainers, and masseurs who revolve around the core group, forming a kind of protective belt that isolates the player from certain realities of the club, which can become increasingly distorted over time.

—Let’s not forget the fan or "supporter"...

—Not at all. The hincha (supporter) is a highly important figure, though unfortunately marginalized today. The supporter, frustrated by the team’s lack of effectiveness, sometimes reacts with intense violence, scapegoating his favorite player—the final link in this chain of conflicts we have discussed. The disappointment of the hinchada (fan base) is immense because the gap between their aspirations and the team’s actual performance is also immense. That is why they fundamentally feel betrayed. We must also consider that their expectations are closely tied to their own understanding of ball control and game strategy.

—Doctor, it is clear that through your insights, we can delve deeply into the study of sports and, particularly, football.

—I am fully prepared to do so.

And thus, our dialogue concluded, though it became evident that we had only just introduced the subject. We later submitted a questionnaire to Dr. Pichon Rivière, who kindly agreed to analyze it. In it, we explored sports in their broadest aspects—beginning with their definition, moving on to the role of an athlete, and concluding with an analysis of Argentine football from this perspective. In the upcoming issues of our magazine, we will present this material, which will undoubtedly serve as a valuable reference point.

Enrique Pichon Rivière

(From Psychology of Everyday Life, 1966/67)